Stef Will

• 13 February 2021

OOO – Do objects have a soul?

I have always been interested in what happens to our ‘essence’ (some would call it ‘soul’) when our physical body eventually gives up on us. This is of course an ever more relevant question right now. I have had many heated discussions about this topic with my 19-year-old son, who is a medical student and very much of the opinion that we simply cease to exist once our body dies. That’s it, no if’s no but’s.

Personally, decades of working as a doctor have convinced me that our main ‘essence’ (consciousness, if you will) survives our body’s death. And I mean this in a very much matter-of-fact, non-religious way, as I am sure that at some point, science will provide us with clear evidence on this, the same way we started to measure our brain’s and heart’s (invisible) electromagnetic fields and these are now a mainstream medical investigations (EEG and ECG respectively).

And I expect to hear scientific confirmation one day that our consciousness is really quite independent of our body. It uses the body as a temporary home, for sure, but ultimately can exist separately from its physical case.

So, if we assume that consciousness really is the all-important essence of us, and that it can exist separately from our body, then that opens up a whole range of other questions. Like, do only human beings have this ‘essence’ or do other living beings like animals, have it too? If we answer yes to that, what about non-animal living things like plants? And what about non-living objects like a stone, or the tea mug I see in front of me right now? Bear with me, as it turns out I am not the only one pondering these questions!

Last week, we had a research day during my MA Fine Art course and while foraging further and further into the rabbit hole that is my university library’s catalogue with all its digitised academic books and articles, I came across an interesting article that discussed the essence of objects in much detail (The Essences of Objects: Explicating a Theory of Essence in Object-Oriented Ontology by Howdyshell Stanford. Published in Open Philosophy 2020, Vol. 3).

So, object-oriented ontology, or ‘OOO’ (not to be confused with an ‘out-of-office’ email autoreply 🙂 is a school of thought that essentially rejects the privileging of human existence over the existence of nonhuman objects. The proponents of OOO argue that literally everything, both human and non-human, and both living and non-living (they summarised all these as ‘objects’) have an ‘essence’ of some sort (call this ‘soul’ and it’s gets even more interesting!).

And they argue that there is no hierarchy between different objects. So, my tea mug has as much of an ‘essence’ as I have as a human being. OOO states that no object should be privileged over any other – so, a completely flat hierarchy.

Don’t get me wrong, they are not claiming that all objects are conscious, i.e. aware of one’s own existence. Nor do they argue that all objects are sentient, i.e. able to perceive or feel things. They simply argue that both sentient and non-sentient beings all have an inherent ‘essence’. But what exactly makes up this essence and how can we try to define the essence of all objects?

I think we may be able to agree that every object is in existence. And it exists in autonomy for that matter, even if we give it zero attention. My tea mug’s autonomous escapades in our dishwasher for example, never crop up until I start pondering it, but just because I don’t think about it, has little consequence for the autonomy of the mug. The same can be said for thousands and millions, even zillions of other objects that exist around us without any hierarchy of existence, as the proponents of OOO argue.

I found it fascinating reading up about OOO, which essentially is dedicated to philosophically exploring the reality, agency and even ‘private lives’ of non-human (and even non-living) entities. The world according to OOO is one full of things acting on one another in a non-hierarchical manner. And we are told that the essence of any object cannot be dictated by human consciousness or even be dependent on human experience. This completely rejects the traditional anthropocentric way of thinking about and looking at the world.

The considerations and possible consequences of OOO are of course highly relevant to art, too. While the default mode in contemporary art is for the viewer to try and read an artwork in terms of the artist’s intentions when making the work, this mode of thinking about art completely ignores the agency of the art object itself.

If we look at a work of art from OOO’s perspective, the artwork’s status as an independent thing must stand separate from its creator. Proponents of OOO would argue that the artwork acts directly on its viewer, completely independent of the artist, and that this is a property that all objects possess in themselves.

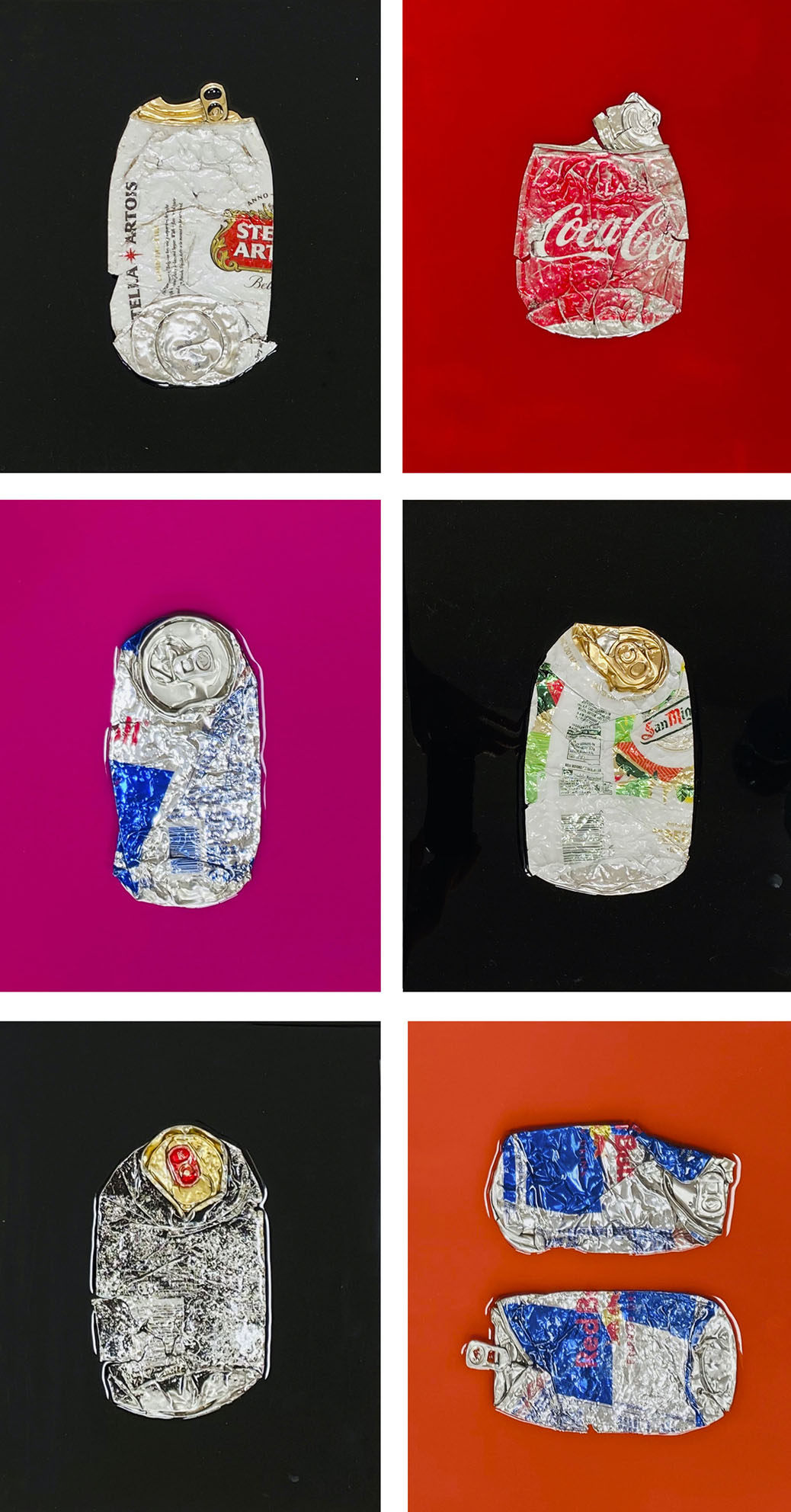

I find this a very interesting way of looking at the world and at art in particular. In fact, I had already explored this subject matter in my work, before I even knew OOO was a thing. In my artwork ‘Essence’ for example (the title is complete coincidence, as I named this, before I had come across OOO as a philosophical theory), I looked at the inherent essence of drinking cans and asked whether their essence leaves the physical object at any point during their decay. Collecting, assembling and looking at these, I strongly feel their essence is present independent of their state of decay.

Coming back to the paper I mentioned above, the author rightly feels that we need a better definition of OOO’s essence of all things. He postulates that while each object has a unique way of exerting itself in the world, it’s actually the local relations of its component parts that make up this unique profile that are essential to its essence. When we look at an object, we may not necessarily see the particular set of relations that forms this object (only the properties of the full object), however the relation of its individual parts is what Stanford feels is vital above all. So far, so good. However, Stanford goes on to state that if for example we had microscopic vision, we may have perceived the object with its component parts very differently.

… and this is where he lost me, because this would then mean again that the essence of an object is very much dependent on the viewer, and therefore anthropocentric at its core, which is against what OOO actually stands for, as Stanford implies that the inherent essence of the object may not be independent of the act of human perception after all.

I will leave you with that. A complex topic, but one that I will be fascinated to continue exploring in my work.