Stef Will

• 5 September 2022

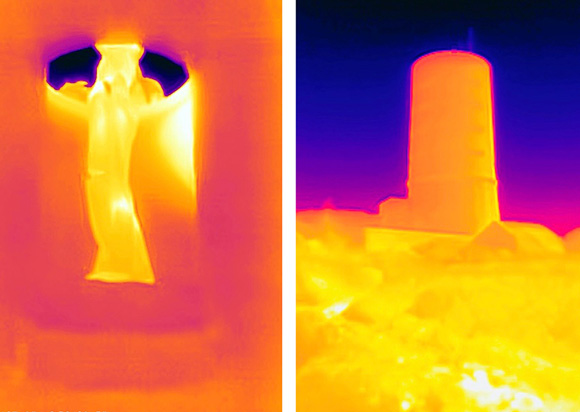

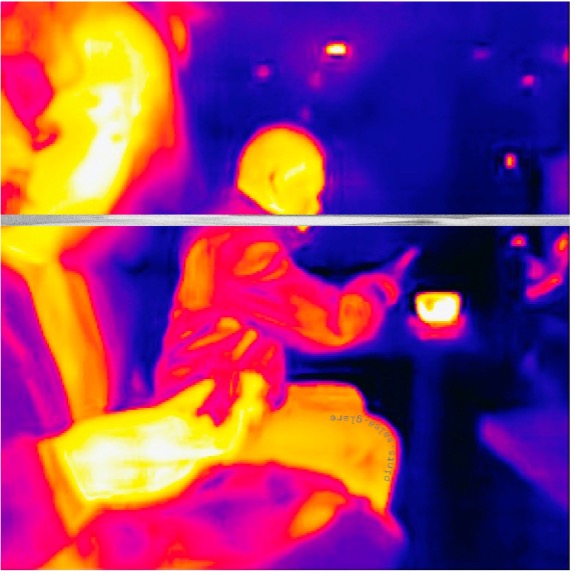

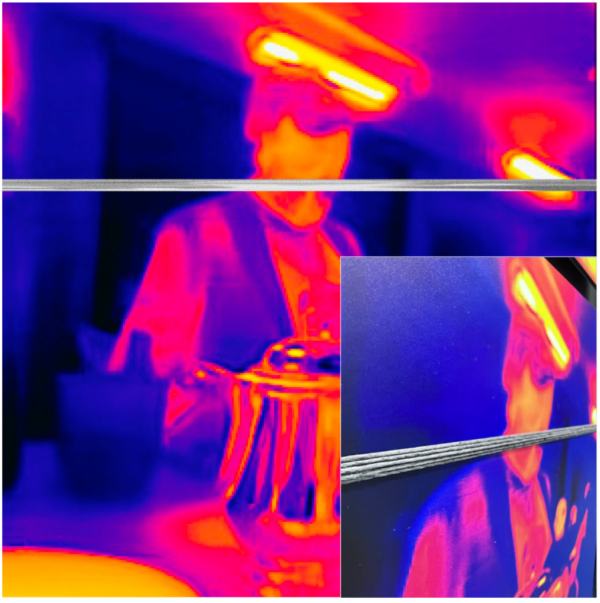

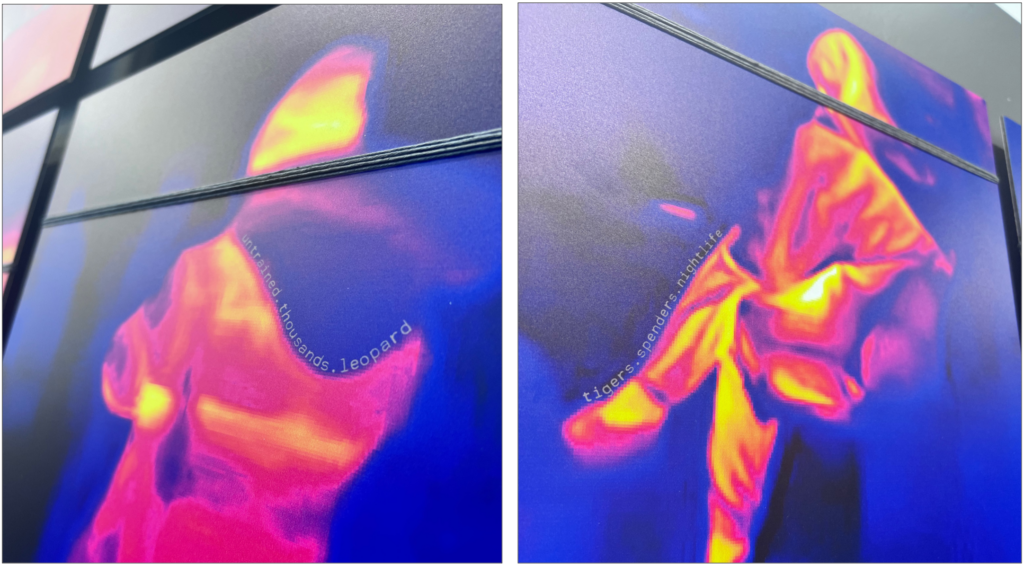

The grey thread of censorship

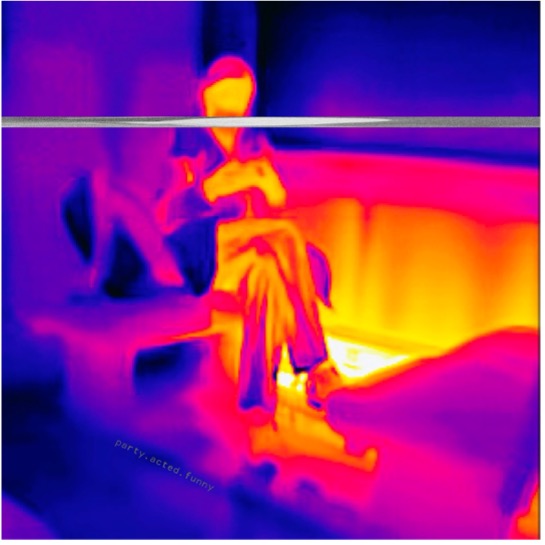

… following my last blog post here, I would like to talk about some details of the art installation ‘Untitled (111 Subjects)’, as a lot of research and thinking went into it. Let’s start with the grey bar that goes through every image. As you can see, each thermal photograph in ‘Untitled (111 Subjects)’ is disrupted by a hazy grey, horizontal bar that appears at different heights in each image, creating a barcode like pattern in the overall installation. Albeit covering the mouth rather than the eyes of subjects, the grey bar is reminiscent of the privacy protecting black bar in anonymised press and police photographs, while its low-resolution, grainy, ambiguous nature reminds of satellite surveillance imagery. When looking at the installed grid of all 111 images in situ, the monochrome bars may also allude to blackened out words in censored texts.

The horizontal bar is generated by overlaying the head area of the subsequent subject onto the mouth region of the previous subject, referencing the escalating censorship of opinions dissenting from official government line, often conveniently denigrated as ‘misinformation’ or ‘disinformation’. In this context, I often think of Austrian philosopher Karl Popper, who warned in his 1945 book ‘The Open Society and Its Enemies’ that “the way of science is paved with discarded theories which were once declared self-evident”, so the last couple of years’ practice of suppressing scientific and medical opinions that are inconvenient (don’t get me started…), is a very disturbing one that does not bode well for the future of neither science nor a civilised, free society.

Coming back to ‘Untitled (111 Subjects)’, the monochrome bar connects different subjects, referring to the concept of peerveillance* (a term coined by yours truly…), further abetted by a grey wax thread tightly wrapped horizontally around this area of the image in the installation, binding the subject in a ritualistic manner. The manual wrapping in the installation hides the digital grey bar, playing with revealing versus concealing, while exhibiting the importance of process and ritual in my work. The recurrent hybridity of analog and digital features found in my work is significant, as it dislocates boundaries and disrupts binaries, such as original versus reproduction, handmade versus digitally produced, mass versus individual, big data versus intimate knowing. The thread also reminds me of Tim Ingold’s words, who describes in his fascinating book ‘Lines’ from 2016, how “through the transformation of threads into traces, surfaces can be brought into being. And conversely, it is through the transformation of trances into threads that surfaces are dissolved”.

Hidden within each image are three, seemingly random, words. These encode the exact geolocation each subject was encountered in, while the carefully chosen typography is that of the typewriter once used by the STASI (former communist East Germany’s ‘Ministry for State Security’). To quote Tim Ingold again, “it is though handwritten lines continued to wriggle around, refusing to be quelled by the objectifying duress of visual surveillance. Only with print, it seems, was the word finally nailed down”. Referencing the STASI in the context of my work is not only relevant because the STASI was an archetypical organisation exploiting peerveillance as a chief strategy, but also because having grown up in (West-) Germany and experiencing the reunion with subsequent aftermath in situ, furthered a more personal understanding of this subject matter and its significance for today’s autocratic mass surveillance measures, not to mention the hereditary dept and cultural burden of Germany’s dark encounter with totalitarianism during NAZI times.

Evocative of the code names that may encrypt clandestine mass surveillance programs of government’s intelligence agencies, the 3-word-codes in ‘Untitled (111 Subjects)’ encrypt information that on seems assessable only to the privileged few who are in the know – the ones with access to the decoding algorithm. However, in this case the decoding algorithm is publicly available in the form of a phone app (what3words), therefore defying the espionage code of conduct.

The three arbitrary words denominating each subject’s geolocation on the planet may also remind of a dada poem, although at times they are unnervingly fitting (or explicitly unfitting!) to the situation, such as ‘visits.trial.over’ for the very last subject, or ‘party.acted.funny’ for subject 86, a middle-aged woman sitting calmly on the train, reading, in Suburban Hinchley Wood, Surrey.

* Surveillance: ‘sur’: French for from above; ‘veiller’: to watch. As we are now being tracked and traced, watched and monitored, observed and analysed more than in any previous time in the history of humanity (sleepwalking towards a hypercontrolled society of technocratic totalitarianism), I am very interested in the concept of surveillance as well as something I call ‘peerveillance’. A hallmark of totalitarian regimes, peerveillance asks people to assist the state’s vertical control system by surveilling and informing on their peers. Peerveillance was of course a technique that the STASI rendered to perfection, turning ordinary citizens into a network of informants, however, peerveillance is alive and kicking, as evident by for example the police’s appeal to report people who breach covid ‘rules’ to the authorities during the past two year. In my part-time role as a doctor, our medical clinic for example was reported to the police (who promptly turned up to check that all was ‘in order’…) by one of our residential neighbours (we don’t know who), informing the police that we were (supposedly illegally) open during the second UK lockdown.