Stef Will

• 31 March 2021

Blood & Art (don’t read this if you are squeamish…)

My (art) work often looks at the electromagnetic energy field surrounding the human body and I am fascinated by how it may be this field that creates the matter of our physical body, rather than the other way around.

Albert Einstein went even further when he said: “There is no place in this new kind of physics for the field and matter, for the field is the only reality.”

In my mind, this energy field is our ultimate ‘life force’. Having said that, the other type of ‘life force’ (the physical type that is, sorry Albert…) for us humans while in body is of course blood. I was really interested to read an article on blood and art the other day, as it discussed the many different cultural meanings and connotations blood has in our society.

Let me start by saying that in our current Western culture (which has become rather ‘sterile’ overall, increasingly so right now of course), we don’t see much of this precious ‘life force’ in everyday life any longer. While in the past, blood was much more a part of ordinary life (think injuries from manual work, barbers who also functioned as surgeons of their time, re-usable menstruation ‘pads’ etc.), blood these days mainly makes an appearance in the virtual world (rather a lot of it for that matter, if I look at my sons’ video games…).

However, despite the fact that blood has more or less disappeared from our everyday life, we are still very much preoccupied with blood as a symbolic representation. Specifically, blood is connected to the following five themes:

1.) First and foremost, blood of course remains viewed as a fundamentally essentialist substance, i.e. the ‘essence of humanhood’ – the life sustaining basic life force of a person, as discussed above. So, in that respect, blood is very much a symbol for our physical embodiment.

2.) Thinking of expressions such as ‘blood lineage’, ‘it’s in my blood’, ‘blue blood’, ‘pure blood’ etc, blood also serves as a frequent reference to genetics, race and ancestry. (please note that I am not endorsing these concepts in any way, but simply summarizing the cultural connotations that can be observed)

3.) Blood also seems to be a symbol of community and social solidarity. Think of the expression ‘blood brothers’ and the altruistic concept of ‘donating blood’ and you get the gist.

4.) While many of the themes around blood (such as community) are positive, blood can however also be perceived in a negative and at times even threatening way, for example menstrual blood may be perceived as a symbol of contamination and/or uncleanliness. I would hope that this is increasingly less so the case these days, but in certain cultures, menstruating women may still be excluded from certain activities.

5.) Last, but by no means last, blood is an exploitable resource connected to power, control and surveillance. This is most noteworthy in blood being an important source of DNA, which contains our entire genetic code and therefore a huge amount of information about the person, their health, heritage etc. Most people would understandably be reluctant to share this degree of information about themselves, especially for commercial reasons.

Working at the interface of art and science / art and medicine, I myself have referenced or used blood in some of my artworks because of its cultural significance and symbolic richness. For example, in reference to a permutation of bullet points 1,2 and 5 from above list, I used three drops of my own blood (safely embedded in resin) in place as my signature on a piece of work. In other artworks I referenced blood when exploring the manifold anti-Covid measures implemented by the government (see below).

There also have been other artists over the years who have used or referenced blood (real or artificial) in their work, including Tracy Emin’s ‘My Bed’ (1999), which contains blood-stained underwear, Kiki Smith’s ‘Blood Pool’ (1992), Portia Munson’s ‘Menstrual Print With Text’ (1993), which shows Rorschach type images made from the artist’s menstrual blood, and Robert Sherer, who drew with HIV-negative and HIV-positive blood.

Blood is a material that that I find fascinating and that I will almost certainly continue to explore in my (art)work going forward. Watch this space…

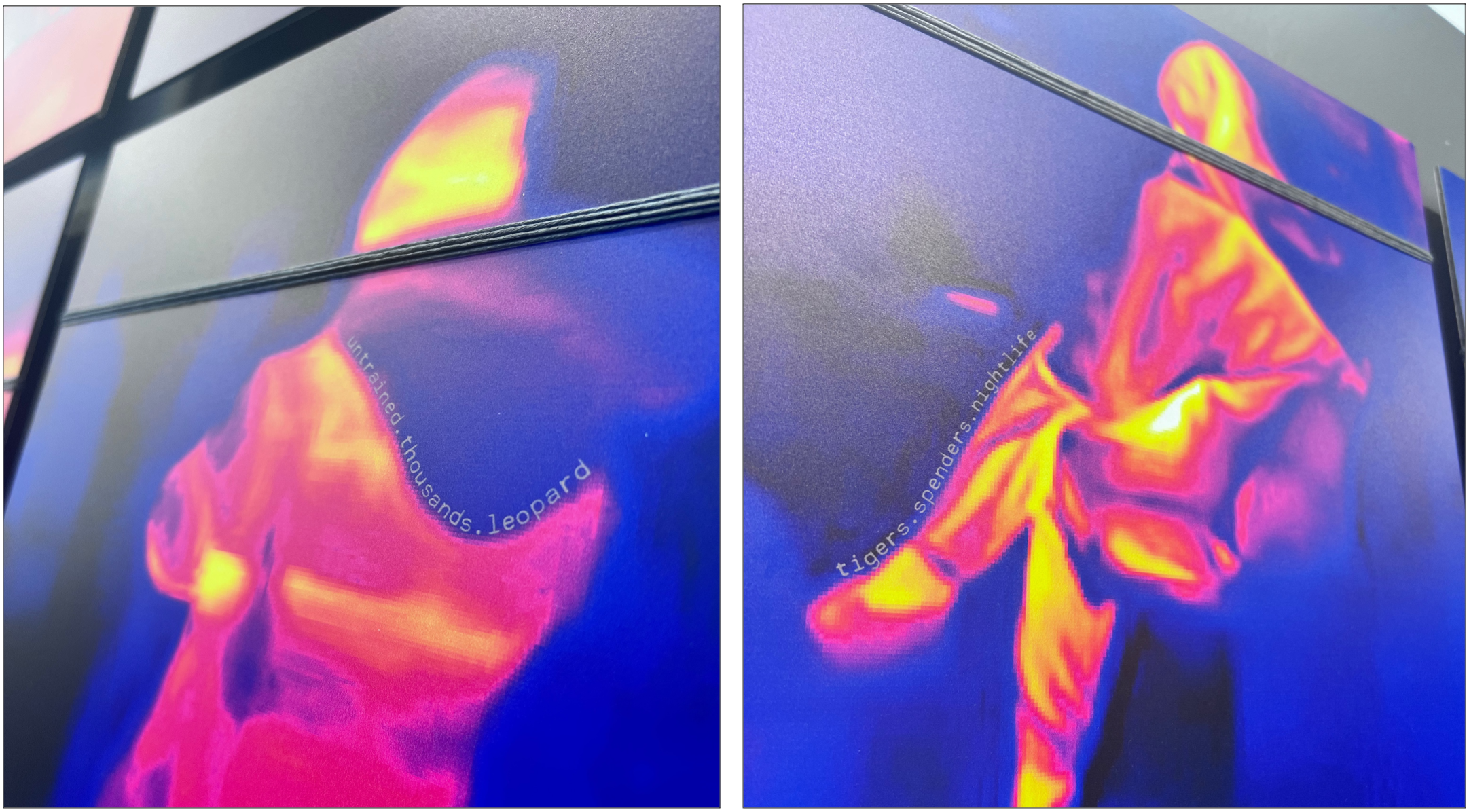

‘Untitled (111 Subjects)’ investigates the algorithmic gaze in relation to power and control. In just over three months, I covertly observed, indexed, and archived 111 people unintentionally encountered in public spaces, following a set of self-imposed rules of engagement. The work appropriates the surveillance aesthetics of the thermal lens to invite conversations about structures of power and control. And the project was of course performed in a distinct period of history, one of global introduction of autocratic control measures under the guise of ‘safety’.

In addition to being covertly photographed using a far-infrared camera, each subject’s skin temperature was measured (contactless), and a set of observational data was documented.

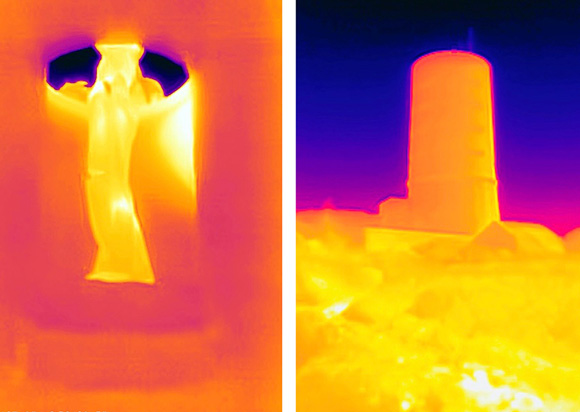

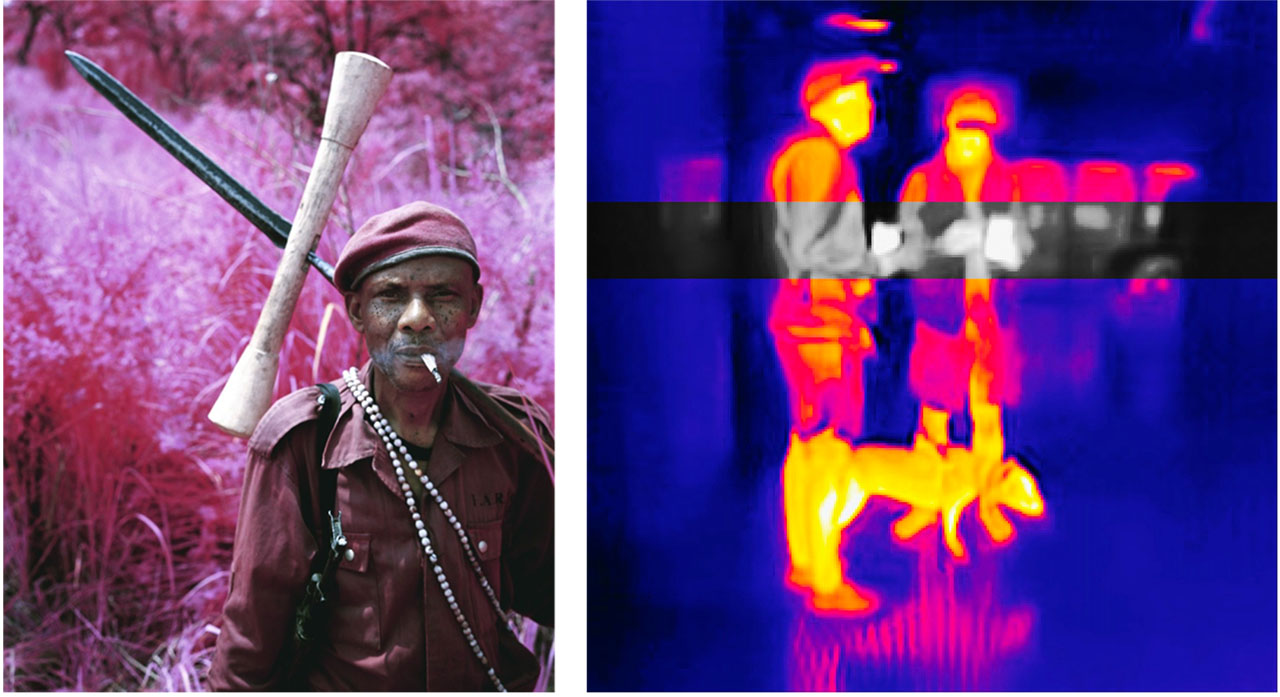

Infrared imaging is widely used in CCTV, surveillance, and night vision systems, and has been employed by other artists such as in Richard Mosse’s project ‘Infra’ (2012), documenting the conflict in Eastern Congo (below left). However, the infrared camera used in ‘Untitled (111 Subjects)’ detects radiation from in the far-infrared region of the electromagnetic spectrum (below right), while traditional night vision cameras cover the (higher frequency and therefore much closer to visible light) near-infrared region. Therefore, in contrast to near-infrared cameras, which effectively still show the visible and touchable surface of the body, the far-infrared lens used in ‘Untitled (111 Subjects)’ makes invisible aspects of the body and objects in the landscape visible, namely the thermal energy field surrounding these. The latter therefore allows the viewer to see things that are normally not seen, but felt (i.e. heat).

As the thermal energy field surrounding the subjects’ body in ‘Untitled (111 Subjects)’ is poorly defined, even merging with its surrounding, far-infrared images appear diffuse, leaving the human figure looking unfamiliar and ambiguous. This unfocused appearance speaks of dematerialisation, a heritage shared with dematerialisation of the art object in conceptual art. The low-resolution aesthetics in ‘Untitled (111 Subjects)’ also advocates against the fetishisation of high-definition, perfect images. Focus and resolution “as a class position”, as Hito Steyerl calls it, leads to the modern-day hierarchy of images, she says. The ‘poor image’ on the other hand, is according to Steyerl, the underdog of images, a non-conformist rebel, a marginalised maverick, experimental, even revolutionary in its nature, and therefore supporting disruptive movements of thought.

I leave you with that thought for today, but there is so much more I want to tell you about my work, for example about the curation, the accompanying audio, the double-wall with one-way mirror etc etc. Watch this space!